No Soap, Radio

Happy New Year from Huell, Elton, and Arthur. Photographed on a 4”x5” sheet of Ilford FP4 with an ‘80s era Fujinon 120mm lens and a level-3 diffusion filter in front of the lens. Posing cats is hard; this photograph took two days and four attempts to make.

It’s been a quiet couple of months for this newsletter. This is mainly because I have been working with an enthusiastic and talented group of young web designers to port all of my newsletters (among many, many other things) over to a new portfolio website that I launched last week. I didn’t want to add to their workload by writing more! You can now find all of my most relevant and recent work at http://gumaverse.com.

We were working together as part of a competition called AIR (Accessibility Internet Rally), which prioritizes and promotes building an internet that is more accessible to all, including people who may be deaf, blind, or otherwise disabled, and who may use tools like screen readers and magnifiers to browse the web. The team got to flex their knowledge and skills about accessibility (e.g. text size, font legibility, color contrast, tab key indices, “alt text” (the descriptive text that accompanies an image file), video captions, audio descriptions, and so much more), and I got a hell of an education as well as a beautiful new website out of it. The site has been submitted to a panel of judges to be graded based on these features, and we’ll know in January how we did compared to the other competitors.

My team did an amazing job of interpreting my goals, one of which was to create a home for my work that feels like both an archive and a museum, and which allows me to express all of the meta-textual information (like technical specs and behind-the-scenes shots!) that make the act of creation so interesting.

Please check back often, as I am doing my best to make this website my de facto digital presence. I’m sick of swimming alongside ads, algorithms, and now AI-generated content. I have left only a ghost of an imprint on my Instagram profile, and if I can stop answering vintage motorcycle maintenance questions on Reddit in 2025, I will be at last fully detached from digital social media.

New Year, Same Everything

I don’t care for resolutions, “Dry January,” or really anything that seeks a temporal excuse to attempt a change in behavior. We should be developing the willpower and strength to pivot ourselves at present, which, if you didn’t know, is at literally any/every point in time. But even though time is arbitrary and invented, I appreciate having a marker—such as New Year’s Day—which can serve as both a deadline and a springing point.

Last year, on the last two days of the year, we shot the Psychic Temple music video for Doggie Paddlin’ Through the Cosmic Consciousness, and I was elated by the experience. It almost felt like cheating; that during a week when almost everything slows down or stops completely, I managed to do two entire days of profound and edifying creative work. Those two days led to many more hours/days working on that project in the following year, and I really enjoyed the feeling that I was able to continually reap from last year’s last-minute sowing.

This year, for those reasons and others—including the fact that scheduling six people at once is a logistical nightmare, except apparently on a holiday week—I decided to pull it off again. December 30 and 31, 2024, we tracked seven songs for a new Guma record.

I got back to writing songs in 2024, for better or worse, and that meant trying to find unique ways to record and represent those songs. My longtime collaborator and friend Gary Calhoun James (pictured holding the bass) finished building out the space in those pictures last year, and since he’s been eager to use it, it made sense to record there. But deciding on the players and the location only takes a few variables out of the equation and introduces many more.

For one, it’s at least a little bit ludicrous to record a 4-and-1/2-octave marimba right next to a drum kit, unless you want the sound of the marimba in every single drum mic (and the sound of an entire drum kit in the marimba mic). Putting a horn player in the room guarantees that whatever they play ends up in every mic. This effect is called “bleed,” as sounds that are intended for one mic “bleed” into another(s).

So what’s the issue? “Let it bleed,” as the Stones album title says. Different styles of music benefit from different approaches in the recording studio, but in truth, there is no fundamental issue with bleed. Recording engineers around the world, including many who have made #1 hits and won big awards, I’m sure will disagree—they can be a contentious type. And there are certainly limitations that arise when recording in this way. But a limitation is just another word for boundary is just another word for guideline. As an independent artist with few resources, my whole career could be defined in terms of limitations; instead of avoiding them, it’s better to pick the most prescient ones and lean into them.

If you commit to letting it bleed, the main concern during tracking (recording) becomes the arrangement of a tune. You cannot, in this scenario, decide later to replace that marimba with a different instrument, or delete the marimba solo entirely. The sound of that instrument is already in every other mic—you’d have to delete everything and start over! This has dual effects, both of which I think strengthen the final art form: one is that songs get “decided” early on in the process, which leaves less room for indecision, doubt, and uncertainty later on when you’re overdubbing and have the ability to add as many things as you want. And it also raises the stakes for everyone in the room as they understand that whatever they’re playing is meant for keeps.

Playing in the same room together means that we can interact more like a band actually does: no one is isolated by wearing headphones, everyone can see each other, and the most powerful aspect of playing music—its ability to connect minds conversationally and transcend verbal communication—is put at the front of the line.

It also means that everyone is forced to play quietly in order to listen to one another, and this is actually a huge benefit to recording. Most people do not realize that even records that sound gigantic and heavy are often recorded very quietly for the sake of the sensitive electronic equipment at work. It’s true that some things, like drums, can impart more energy and momentum when they’re played at a higher volume, but almost everything else benefits from quiet recording. Jimmy Page’s guitar parts on the Zeppelin albums are well-known to have been played through amps that were not much bigger than two shoeboxes stacked on top of each other. Contrast that to the huge amp stacks that you see on stage and what your ear thinks those records sound like. The point is that recordings can be later mixed to feel huge and loud, if that’s what’s needed, but that playing quietly almost always benefits the technical aspect of the recording.

But quiet playing is no easy feat even for one person, and in a room with six people it’s going to be inevitable that no one can hear all. There is a subtle psychological benefit to this, as players sometimes reach to fill space individually and meet each other in interesting ways.

Another factor at work is that there is no regular Guma “band.” All of my recording projects are assembled ad hoc, and while this allows for great sonic and creative freedom, it means that no one except for me has any familiarity with the material (and I’m not always sure that I like what I like). This works both ways: you can capitalize on peoples’ spontaneous reactions to novel compositions, but it means you have to do some amount of rehearsing on the spot before you can record anything. You don’t want to rehearse too much and have folks lose their sparkle before the recorder is even rolling, but you need to rehearse enough for everyone to understand the structure and intent of the song.

There are too many chord changes in all of these songs. It takes a little bit of time to get everyone on the same page

The person in the driver’s seat (me) needs to be prepared to answer questions, make decisions, and direct the scene, all while keeping in mind that the raw materials we’re working with are human beings, and artists no less—delicate, sensitive, emotional. You gotta be nice!

And so we played Guma music for the last two days of the year, and I hope my collaborators felt, as I do, that it was a splendid way to spend an otherwise dull and slow time of year. In all, because most modern “song” records are no longer made this way, I hope that our approach lends a unique quality to this set of tunes that sets them apart from other music and even other Guma albums. My goal is always synthesis: of my own past with my current preferences, and of the larger historical past with my understanding of my own present. We’ll find out how we did in 2025.

What Am I Watching?

I used to think that vampires were among the lamest of supernatural creatures, but in 2024 I think I pulled a complete 180-degree turn. I’m all in on vampires these days, Robert Eggers’s Nosferatu notwithstanding. Let it bleed, as they might prefer!

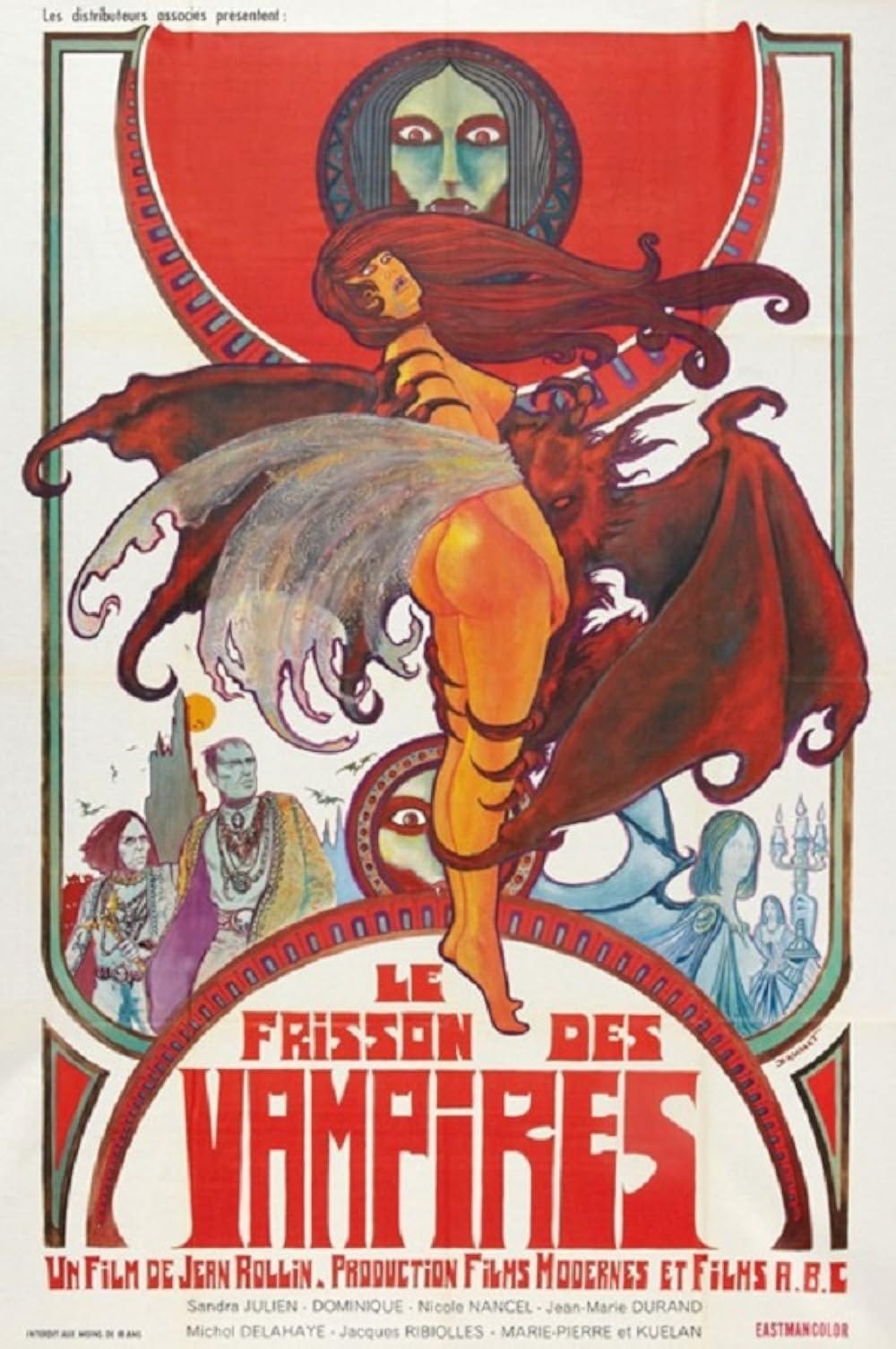

In 20+ years of seeking the strangest (and often trashiest) cinema, I don’t know how I missed director Jean Rollin up to this point. He made plenty of films, starting in the late 60s with a quartet of erotic vampire films. His third, The Shiver of the Vampires (1971), finds him cruising comfortably in his lane. A newlywed couple travel to an ancient castle where the last of the bride’s family—two male cousins—live together. Upon their arrival, they’re informed that the cousins have died and were just recently buried. In shock, the bride insists they stay at the castle only to discover that the cousins are not, in fact, dead—although it seems to be only at night that they’re available for socializing, strangely enough. It turns out they were formerly the best vampire hunters in the land until they messed up and got turned, and now they are the most moral vampires around: they insist on destroying each one of their victims with a wooden stake after feeding so that they don’t contribute any more to the rising vampire population. The bride, desperate to hold on to the last of her family—living or otherwise—rejects her new husband’s pleas to depart, and they’re both drawn into the very sensual, very strange, very French situation (did I mention two male cousins who live together in an ancient castle?)

Make no bones about it, this movie is “bad” on a number of levels, and so are all of the Rollin films I’ve seen so far. But it more than occasionally has striking cinematography, bold and unnatural colored lighting for which the Italian gialli directors often get the most credit, and it’s packed with naked, undead women.