Swimming with the Fishes

On subscriptions, followers, attention-based economies, and what's next for me

“Have you heard of Twitter?”

“You would be great on Instagram; the visual component suits you.”

“The band is not posting on Facebook enough; we really would like if you could do regular content.”

“You should do a Kickstarter!”

“Have you thought about starting a Patreon? People are really making a living with it.”

“I hear everybody’s moving to Substack; it’s a way to share things with more nuance.”

When I was in high school, everyone had a LiveJournal. It was a small digital home with just enough tools for creative expression—namely writing, but also primitive page design, color choices, profile pictures, etc. Friends followed each other in earnest, and would-be cyberstalkers got an early hit of being able to look someone up, crawl through their public private life, and project all manner of assumption and phantasy onto that person. For many, it was the first scratch of a digital itch that has only grown in the 20 years since: a collective egoism, voyeurism, and the early buds of what would bloom into a phenomenon we call “FOMO.” The capitalists, as always, were standing by for their moment.

A blog by any other name…

And now I have a LiveJournal again—er, a “Substack”—and what’s different is you can pay me to read it. Or not. Though I shouldn’t say that—or what was it the “Getting Started” page recommended? Hold on, if I enable a certain pop-up it’s supposed to encourage 10-20% more of you to fork over some cash, statistically proven. But wait, give me a second to set up the “Founders Plan” so you can give me more—I mean, only if that’s what you wanted to do in the first place. Actually, just pay what you want, even zero! Now this is a buyer’s market!

Here’s the rub: I love to write. Before I ever wanted to make music, before I wanted to make films, before I wanted to be on the radio, I wanted to write books. But content is not literature, and blogging (“live journaling?”) is not writing per se. So why am I here? And what will I do here?

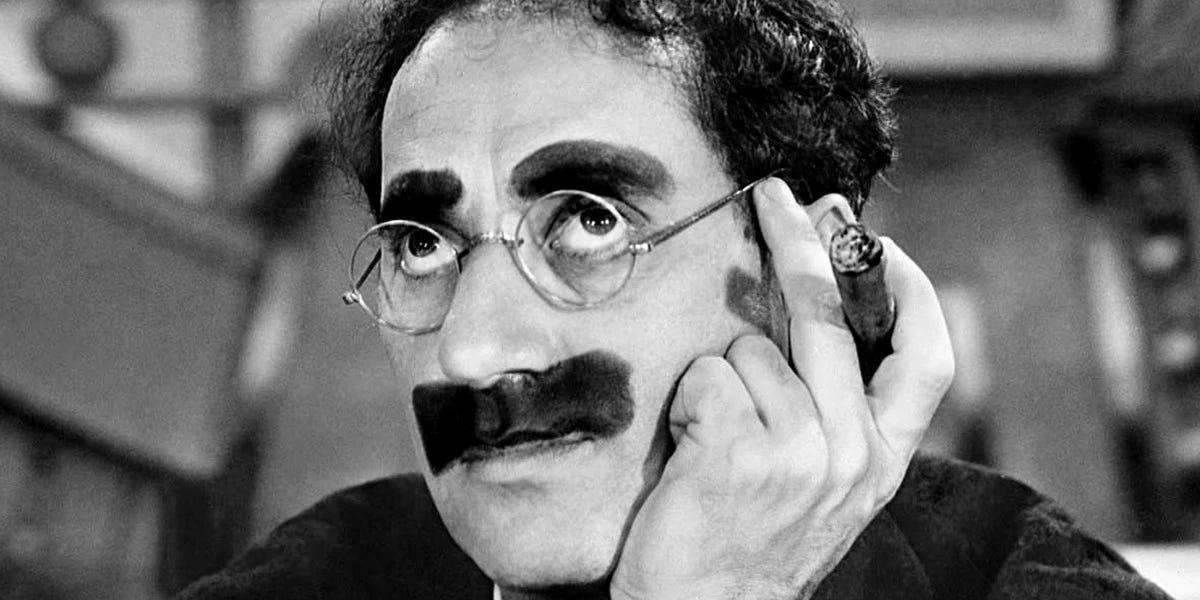

“I don’t care to belong to any club that would have me as a member.”

This concept was introduced to me in a direct-to-camera address by Woody Allen in the film Annie Hall, and though it’s no longer socially acceptable to credit Allen with anything but moral ineptitude (in the most generous case), the film remains a masterpiece, and the quote—attributed to Groucho Marx—remains universal.

The keynote speaker at this year’s SXSW conference was Jack Conte, founder of Patreon dot com. He is an energetic, optimistic, vibrant personality, and he is my peer in the sense that we are a similar age and have navigated our artistic careers under similar global circumstances, namely the rise of the Internet as the medium of communication, distribution, and capitalization par excellence. And he makes a great case for his invention: in this gigantic, digital, monocultural sea, artists need a way to connect directly with the people who are interested in what they do, and people who love art need a way to connect directly with (and support) the kind of creativity that moves them. Win-win, right? I disagree.

This guy is a multi-millionaire and I am not, so that makes me wrong (to some people).

The reason that I don’t have a Patreon for Guma is that I disagree with the fundamental value proposition of Patreon, which is, in a word, “access.”

The Patreon model says, “So you’re an artist, and you want people to consume the art you share. But in fact, you’re not sharing enough. Here is a platform where you can effortlessly post sketches, demos, rants, bad ideas, host livestreams, etc., and for a small cut we’ll make it easy for people who like you to pay you for access to these things.”

But to hear Conte tell his own story about finding his audience online and dreaming up creative ways to interact with, inspire, and bring value to that audience, it becomes clear that he never stopped to answer a pretty obvious question: why should I give anyone access to those things? Making good art is a deeply personal process. It’s hard. I already spent all of my money, most of my time, and called in as many favors as I could to deliver a slab of wax with my art on it—and that’s what I want you to pay for. Why should I “share” every burp, fart, and squeak that happened along the way? In fact, why should you care about Me at all? The art is over there!

It is immediately obvious to me that Patreon just doesn’t work for certain types of artists. As an aside, Patreon also takes for granted that every artist has an imminently tappable fanbase, when in fact the biggest hurdle that all artists face and which has yet to receive any reasonable technological solution is not how to get paid, but simply how to cut through the digital noise to reach somebody, anybody at all. On all large media platforms, content discovery is still gatekept by closed-door algorithms and highly influential (read: clique-y) “editorial” curation. If you watch that keynote that I linked above, I think it’s depressingly telling that Conte’s pivot point toward a crowd-sourced version of success occurs when… *drumroll* he starts putting his girlfriend in his videos.

My god, it’s… a woman!

The “Me” Economy that includes not just Patreon but other crowdfunding websites like GoFundMe and Kickstarter, content platforms like YouTube, and social media platforms like Instagram and TikTok takes for granted that every person needs (and wants) to put their physical and metaphorical Self at the center of their commerce. No matter what you think you are creating, you are the actual product. And unfortunately, we’re all wallowing in it together—audience and artist as equals.

“What’s up guys it’s me here to tell you about this new newsletter that I’m launching! Here’s a cute pic of me competing with conspiracy theorists, mukbang videos, egotistical billionaires, visual artists (human or not), so-called influencers, oh yeah, and other actual musicians for your attention! Make sure you like, comment, and subscribe!”

What has been lost in our collective conversion from an analog to a digital world, from a largely observational to a largely participatory internet, is the notion that art can (and perhaps should) be experienced—consumed, digested, interpreted, bought and sold—completely independently of the artist who made it. Artists don’t “share” things (this is a huge personal linguistic nit that I never tire of picking and should be its own post), we create things. It’s up to an audience to pick up what we’ve put down and do something with it. How else is art supposed to work its magic on your psyche if you don’t have any time alone with it?

Separating the art and the artist: this is a tall order. It goes wildly against the modern grain, and it feels impossible in an age where consumption is the most conspicuous it has ever been and/but is now almost always paired with a value judgment. In other words, not only should we collectively disavow Woody Allen out of objection to the things that he has done personally, we should also cease to enjoy any of his work because of what such enjoyment says about our moral compasses. Never mind that it takes hundreds of people working thousands of hours to make a good film, only a minute percentage of whom are pederasts. Never mind Diane Keaton (at your own risk). Cut to: my wife and I in the kitchen this morning talking about starting a Substack.

“Mmm I don’t know, I think people are bailing on Substacks because the company doesn’t do enough to de-platform hate speech.” “Wait, who is?” “I dunno, maybe that’s mostly blown over now that I think about it.”

From my non-millionaire perspective, the intersection of art and commerce is necessarily doomed. But if I’m already swimming with the fishes, I might as well, well, swim along with the fishes. So to answer the question I posed at the beginning of this piece, I’m here to share some of the ideas and creations with which I populate my world and which don’t really fit into my projects as a musician, or a radio host, or even as a writer. I heard it’s nuanced, you know? And I thrive on nuance.

I am proud of my life, and I do want to share parts of it in ways that are more detailed and personal than an Instagram post. This includes my art and some of the processes therein. In fact, in the service of making good art, I frequently challenge myself to learn new things, and I often feel compelled to share those findings with my people. Not my “followers”—my people. Not “sharing,” but sharing. And why should I charge anybody for that? If you want to support me financially, buy my music and then tell your friends to do the same.

What’s Next

In my deepest moments of existential angst, I enumerate to myself the various irons I have in the fire. And there usually turn out to be a lot, otherwise I get extremely depressed. I hope to use this newsletter to talk more in detail about:

The next Guma album, appearing this year

A short film that I made with a $10,000 grant from the city of Austin in support of this album release

An upcoming music video that I directed, photographed, and edited for my friend Chris Schlarb (Psychic Temple) using a hand-wound, Soviet 16mm motion picture camera

My current obsession vis-à-vis the above: repairing and using vintage camera equipment and the photographs that result

My show on KOOP Radio, now entering its 8th year. You can listen to Small Cool World every single Thursday afternoon on 91.7FM in Austin, TX or worldwide at koop.org

Ideas about art, commerce, and being true to yourself amidst the chaos of social living

The next batch of chicks

No subscription required; you just go to the farm store and pay $4/bird

If you’ve made it this far, I also want to show off the album artwork for the next Guma record. It features a septet of incredible musicians playing two fully-improvised, side-length free jazz pieces while I narrate two spoken word compositions along with the ensemble. Part Ken Nordine, part Miles Davis, part Nilsson’s The Point. It’s called “Riprap,” and you’re hearing about it before almost anyone else.

Layout and design by longtime friend and collaborator Robert Carroll from a sketch I made. 12” LPs arriving this summer.

I’ll announce that LP and start taking pre-orders on the next Bandcamp Friday, the first Friday of each month where that platform waives their cut of sales.

Finally, if you’re getting this first newsletter, it’s because you’re a close personal friend of mine or you’ve come to a show, bought something from me online, etc. In other words, I have your email address. If you want to opt out, go right ahead; I’ve disabled all notifications and won’t be bothered either way. If you want to start a correspondence, you can reply to this newsletter to reach me directly, and I would love that.

But I do hope you choose to stay with me.

What Am I Watching?

I think I’d like to include a short recommendation at the end of every newsletter. I watch an average of just under 200 films per year, which is about a movie every night of the week with weekends off. I love movies, even the bad ones; I think they are so important to understanding our experience of being, and they greatly inform my artistic processes. But great film art is not immune to the same social and commercial forces that besiege great music. I’ll save this for another newsletter, but my opinion is that subscriptions slowly kill your ability to find compelling film art all the while convincing you that you have access to more things than you could ever watch. So you should be satisfied, right?

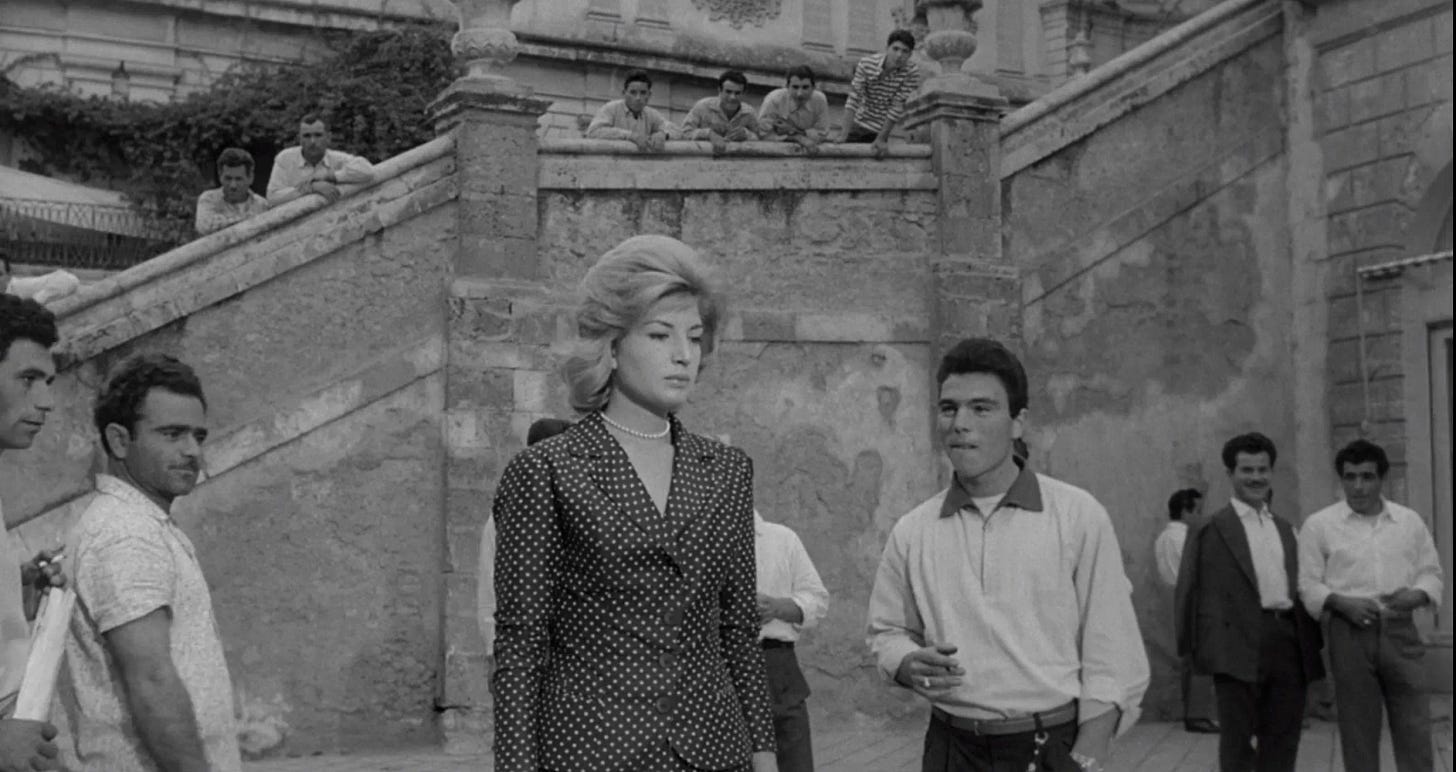

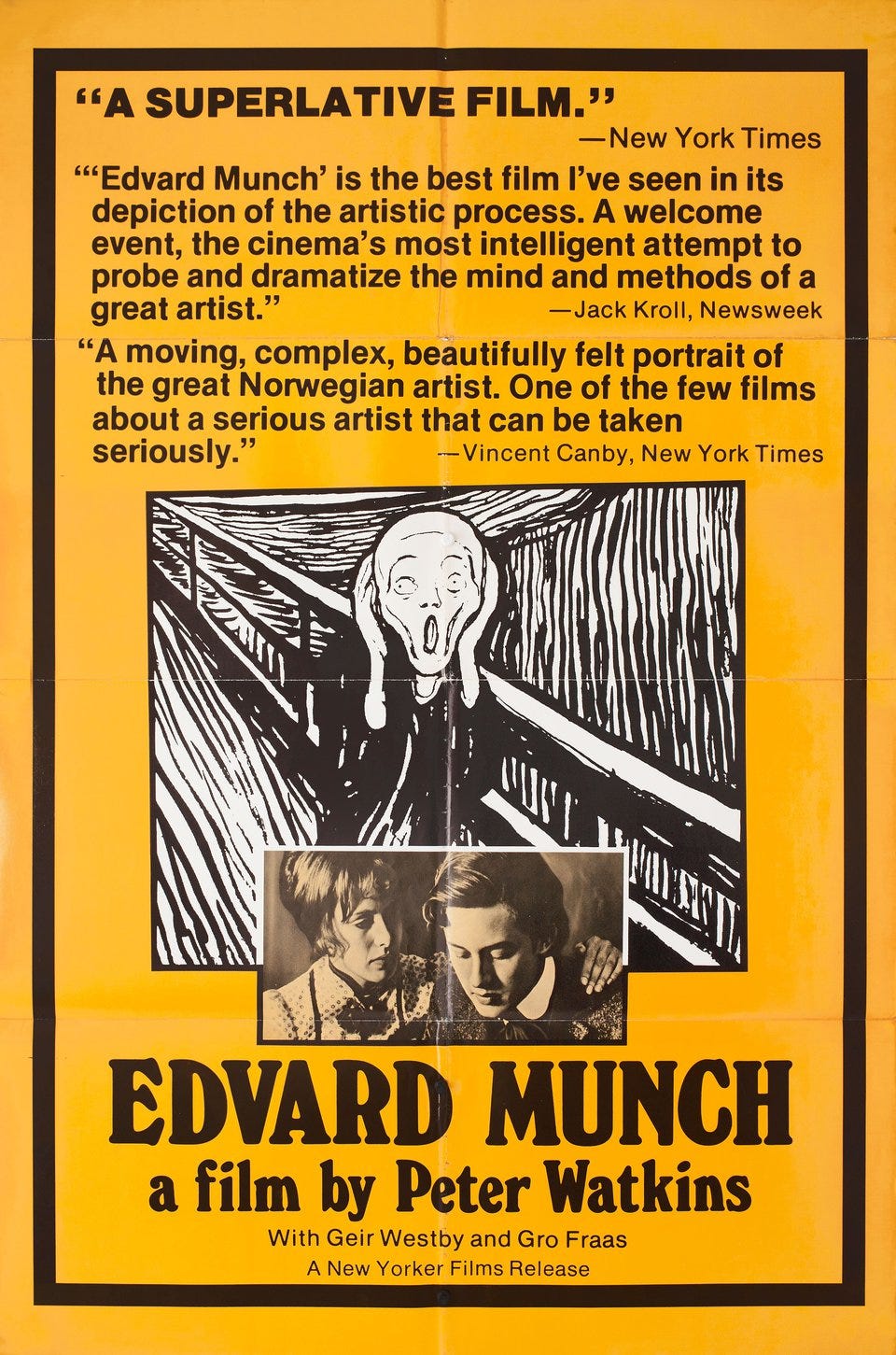

Just after I finished explaining to my mother why I think biopics kind of suck and that I didn’t see myself ever sitting through Oppenheimer, I dove into this 3h42m film about the Norwegian painter Edvard Munch.

Peter Watkins is an English director who pioneered a truly enrapturing style of faux-documentary. His films can hardly be called “mockumentaries” since comedy is not at the center of attention, though they are frequently funny. This film to me represents a high water mark for a style that he developed with films like Culloden and Punishment Park, where, against all historical odds, a camera crew happens to be present to capture incredible historical events and personages, and the people in the films react as indifferently to the anachronistic technology as they might in a modern documentary. His penchant for casting non-actors and shooting with natural light lends these films a fantastical realism that simply does not apply to a more traditional dramatic biopic.

If you can find a copy, see it. And remember that outside of Netflix and Amazon Prime, things like the public library do still exist (and many have paired with Kanopy to offer their digital collections to stream at home for absolutely no charge!).

More! More!