The Hamburger Analogy

Let me get a double cheese, add pickles, grill up some onions, only the bottom bun toasted, extra mayo, ketchup on the side, and if you flirt with me I might even consider paying for it.

I’ve been chewing on something I’m calling the “hamburger analogy.” It goes like this:

Imagine you could walk into any restaurant in the world, order a hamburger, eat the hamburger, and walk out without paying. When the owner of the restaurant stops you at the door and asks you to pay for your meal, you pause, think for a moment, and then decide, “nah, it wasn’t really that great of a burger. I’m just going to leave.”

Or maybe you grab them by the arm and enthusiastically announce, “that was the best burger I’ve ever had! You know what? I’m going to sit back down and order another one!” After you eat the second burger, you wait for the owner to get distracted by another customer and walk out.

You do love burgers, and so you decide to travel across the country and stop into every greasy joint you can find, have a meal, and walk out without paying. You’re not just sampling, either—a bite here, a nibble there—you’re downing burgers left and right, good and bad, affordable and overpriced (not that it matters). And why should you pay, anyway? You already paid off the car you drove to get here, you buy insurance because you have to, and you’re paying for the gas to get you around to all these burger joints. Shouldn’t the owners of the burger joints be grateful to have an enthusiastic customer like you? After all, you might end up telling a friend or two about the best burger they can find in Nebraska, should they find themselves in Nebraska for some reason.

Finally, it catches up to you (not the cholesterol): someone recognizes you and calls the cops, who were on their way for lunch anyways. Look man, you gotta pay for that burger. “But it’s just a hamburger!” You protest. “It doesn’t cost anything, at least not compared to, like, filet mignon! Besides, I’m using an app that lists every burger joint in the country, and all these restaurants have paid to be on this app, and even I paid to get premium access to the newest listings! Why don’t you make the owner of the app pay for my burger? This app has made him a billionaire!”

We’ve all had a great meal at a restaurant, the experience of which transcends just the quality of the food; maybe the price was right too, or the riverside patio view was simply gorgeous during the sunset, or the occasion—a birthday, an anniversary—made it memorable. When the check comes, we don’t think twice about paying it. We’ve all, too, had the unfortunate experience of a less-than-satisfying restaurant meal. “$22 for an overcooked, flavorless patty? I’ll be damned if I ever come back here. Let’s get the check and get out of here.”

If it’s not obvious by now, I’m actually talking about music. What led me to this analogy is the thought that in any other commercial endeavor, the idea that the customer can experience the full breadth of the product that is available for sale—from tip to tail, as it were—and then decide whether or not they cared to pay for it is patently ludicrous. It’s even more ridiculous to think that even someone who enjoyed that burger more than any other burger they’ve ever had could continue to go get that burger without paying for it. Every business has operating expenses: that $22 burger gets divvied up into so many fractions of capital that go toward the ingredients that comprise that burger, the rent on the building, the electricity, the trash service, disposables like cups and plates, and—I should hope, at that price point—a fair wage to the front-of-house staff, the cooks, and the bussers. Even if you were disappointed by the meal, I would guess that with the exception of a minority of ultra-complainers among us, we all would take the loss, pay for it, and not come back. Because food costs money, and we understand that.

Spotify CEO Daniel Ek is frequently blasted by the musician community for his public statements that amount to a position that making music doesn’t cost money, and that musicians who want to make a living wage should simply release more of it (on his platform, of course). But if you stop for even a second to consider the expenses that go into making anything, much less a quality record, common sense prevails. Everything costs money: the recording studio, the engineer, the musicians, the producer, the arranger, the mastering engineer, the visual art that accompanies the release, the duplication house making your tapes, and so on. Much like owning a restaurant, owning a music business involves paying out money to various “employees” (and even bureaucracies—you do need electrical service to accomplish any of this, after all) who enable the business to even present a viable product, much less attempt to market and sell it.

This essay is not written specifically to put Daniel Ek on trial, although as one of the world’s many billionaires who have ridden on the backs of hundreds of thousands of anonymous and unpaid laborers, one could make a compelling argument that we can skip the trial and walk him straight to the gallows.

It’s more about keeping the flame of “value” alive and continuing to appeal to you, the lover, appreciator, admirer, and consumer of hamburgers—er, music—to hold yourself accountable to ascribing real value (viz. cold, hard cash) to the experience that music gives you.

What I lament the most about the streaming era of media is the “platforming” of music in the first place. Earlier this year, I released Riprap on vinyl and digital download to a pretty muted response. I intentionally kept it off streamers because I didn’t feel like the two 18-minute sides were appropriate in a context where playlists are prioritized, ads are sprinkled everywhere, and attentions are usually elsewhere. I wanted people to consume my burger in a specific context and/or medium (rare).

And for over 100 years, music has been available in this way. It didn’t matter if you bought cassette tapes because they were cheap, or vinyl because you enjoyed the snap/crackle/pop, or CDs because that’s the device that your car was equipped with. You had a choice as a consumer, and you regularly paid the market price to consume things that you might not have ended up enjoying after all, like that bad restaurant experience. My feeling is this: music never needed to be platformed, full stop.

Because now it all comes from that one place with historically impressive sound quality: your phone. “Is it on Spotify?” has become the de facto litmus test for all potential new fans. “You’re a musician? Can I check out your stuff on Spotify?” Yes, of course you can, I begrudgingly reply. What I want to say every time I have this exchange with a new acquaintance (or even an audience member at a show who had heretofore not heard of me) is, “fuck if it matters whether or not it’s on Spotify? I made it, didn’t I? I’m standing in front of the merch table literally holding it in my hands. You can hear it at all, or can’t you?”

You don’t have to do too much Googling to discover that the exponentially increasing wealth inequality in the world is reflected almost 1:1 in the music business. The top 1% make the vast majority of the money from a platform like Spotify. I don’t think the solution is to litigate platforms like Spotify into paying more per stream, or to pass laws that would update the laughably out-of-touch Digital Millennium Copyright Act that was passed before most people even had an e-mail address. Those things would help restore some balance to the economic ecosystem of musicians, but regrettably the tower has already fallen.

Because the real funeral here is for value in the eyes of the consumer. Collectively, we have allowed technologists and “platformers” to convince us that we don’t actually need to own anything; that more convenient than a heavy shelf full of records that represent the eras of our lives, our changing tastes, the people we love, gifts, experiences, travels, and memories, that more convenient than the small trifles that amass to form life itself, is to just pay someone to have access to the digital facsimiles of those things. The irony here is that those motherfuckers don’t own any of it either, and my mind cracks if I try to think too hard about how they were allowed to do this. They saw an opportunity to “disrupt” an entire ecosystem of small business owners (viz. musicians) and re-direct the flow of capital from hundreds of millions of consumers to a single destination: their pocket. In my life, this is the single most salient labor/capital issue.

Already, an entire generation of humans has been born and raised in this economic context. They do not know, and many of them will never know, what it means to seek out music and pay anyone—an artist, a small record store, even Walmart—for their own copy of that music.

But we can’t go back to the last century’s hamburger joints, as inconveniently located as some of them may have been. Wasn’t that part of the thrill, though? “I can’t believe I finally found a copy of X! And out here in the middle of Nebraska, to boot!” No, those burger joints are all long closed by now. I’m never eating at this one again either, if I can help it.

What Am I Watching?

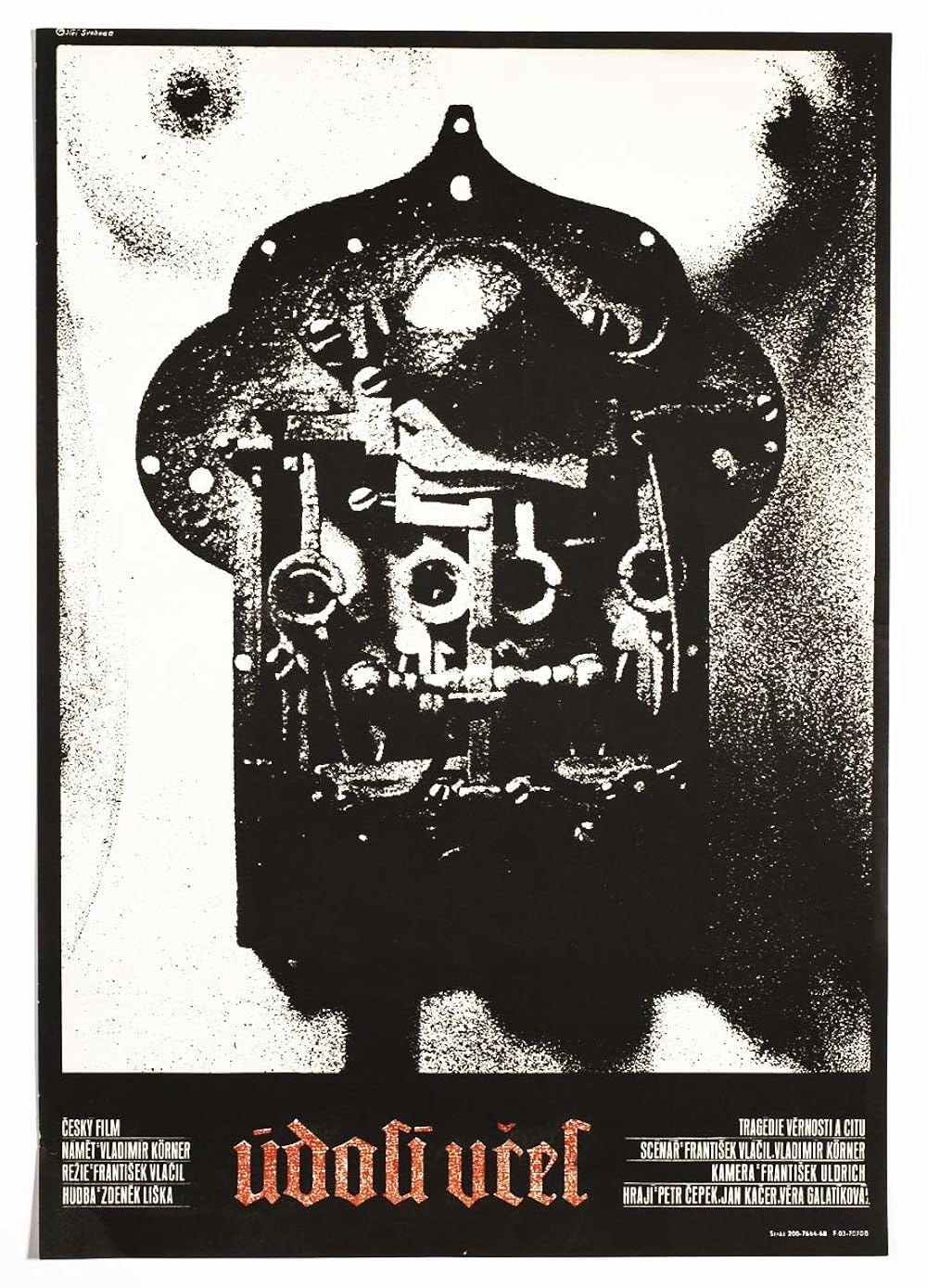

Frantisek Vlácil is credited with creating the best Czech film of all time, Marketa Lazarova (1967). And I don’t disagree with the many expert cinephiles who have elevated his film to that position: it fucking rules.

To my delight, I discovered recently (in my hunt for more witch-burning cinema) that Marketa Lazarova is actually the second of three tangentially-related films that form a medieval cycle in Vlácil’s filmography. They’re the only historical pieces that he directed, and they’re related in matters of concept, form, and style, but also in simple economics: Marketa Lazarova was so expensive to produce and ran so far over budget that Vlácil quickly pulled together a third film in this loose trilogy using the same costumes and some of the same sets in order to make the most of money that had already been spent.

The Valley of the Bees (1968) is this third film, and while it lacks the epic scope of the previous film, preferring instead to essentially focus on the conflicted relationship between two men, it hits all the marks in terms of its historicity, costuming, dreary black and white photography, and plenty of gnarly human violence.

Ondrej is a small boy when his father accidentally maims him in a bout of rage. Feeling penitent, the father gives up his adolescent son to an order of Teutonic knights who raise him in their strict, devoted tradition. As a young man, he forms a strong bond to his fellow knight Armin. This bond is fractured when Ondrej abets another knight who attempts to leave the order and return to his former, heathen life. As punishment, Ondrej is locked in the monastery where he becomes disillusioned and escapes to return to his home village. When he arrives after many years away, he finds that his father has died. But the townspeople remember him and welcome him back to take the place of his father as the head of their small castle. Armin, however, is violently committed to bringing his lost sheep back into the fold, and that’s when the sparks begin to fly (from sword on sword combat, of course).

The Valley of the Bees can seem as strictly formal in its directorial style as Armin is in his devotion to God, and/but this attention to detail is something that I absolutely adore as a viewer. While it stands alone as a fine example of cinema that is worth your time, I also can’t recommend Marketa Lazarova enough, and if that hits the mark for you, The Valley of the Bees is a necessary follow-up.