In the middle of the last century, amid the fastest and broadest technological growth spurt yet known, Marshall McLuhan wrote that content is essentially a distraction from the rhetorical and social implications that are inherent in a medium of transmission itself. A giant nut was cracked, and millions of newly-minted media theorists—psychologists, artists, mathematicians, advertisers, politicians—poured out.

Somewhat ironically (but to be expected), McLuhan’s great insight itself became shorthand for a kind of counter-cultural “wokeness.” I picture this great idea about media—which owes its origin to Walter Benjamin’s work from a few decades prior—arriving on the scene just after television entered many American homes, around the same time the Beatles landed, flourishing amid skepticism about U.S. involvement in Vietnam, and ultimately becoming flattened into a mere signifier of an assumed psycho-cultural hipness.

“Just as water, gas, and electricity are brought into our houses from far off to satisfy our needs in response to a minimal effort, so we shall be supplied with visual or auditory images, which will appear and disappear at a simple movement of the hand, hardly more than a sign.” Walter Benjamin quoting Paul Valery almost 100 years ago. Image screenshot from Apple’s livestream reveal of a new iPad this week

This blunting process is something that cultural theorists call “smoothing.” In fact, the wisdom of the crowd is an age-old idea and has produced many useful tools, some of which (like Wikipedia) I use to produce this newsletter. It’s not an innately pessimistic process any more than calculating the average of a set of numbers is, but it does represent a conceptual “average,” and averages are, well, average.

If you read 20th-Century art and media theorists, you get a sense that there is a smorgasbord of ideas in proportion to the number of emergent technologies. Motion pictures are practically brand new, and television really is brand new. Consumer audio starts the century confined to wax and shellac (or radio waves), and by the end of it there is a panoply of media to choose from, most of which we’ll never see again, and some of which was never even seen by the people who used it.

But in the 21st Century, almost all content has dovetailed—or rather been shunted; “smoothed,” if you will—toward the service of a single medium: the internet. And what’s more, the user experience of the internet has been shaped by the advent of smartphones, touch screens, tablets, etc. and continues to be shaped by technologists with too much money and too few people skills (see: VR, “the metaverse,” and so on). Decoding the message of this medium, which is among the first to substantially incorporate (indeed, necessitate) user input in addition to passively serving content to the user, is a Ph.D.-sized burger that is not the focus of this essay.

Because what I’d really like to propose is that within the context of the Great Cultural Smoothing, the message of almost all media other than the internet has changed and acquired new significance in ways that can and should be leveraged by artists.

The smoothest sphere ever created is made out of silicone and was used to try and standardize the weight of a kilogram as recently as 2018

But first, more on smoothing. Cultural smoothing is interesting to me because it works as a factor of so many processes that all feed into each other to form the “main stream.” The processes are technological, economical, and cultural (that is to say social) in nature, and because of the interconnectedness of the internet, they are global. Let’s take music production for example.

Why does mainstream music all sound the same? It can’t just be because we’re all getting older, though we should try to keep in mind which of our biases are within/out of our control. Here are some simple suggestions, none of which offers a complete explanation:

Mainstream music-makers all use the same software, plugins, instruments, and mixing techniques (technological smoothing)

Consumers have largely foregone the hi-fis of yesteryear in favor of portable, battery powered, cheap, and ubiquitous “smart” speakers (or just phones) with limited frequency ranges (technological + economical)

Most mainstream music is made by a small number of producers (technological + cultural)

The music industry is highly nepotistic (economical + cultural)

There is a soft conspiracy among monied gatekeepers (the record labels/conglomerates of old), technologists and their media platforms (streaming services, social media), and elite artists/producers (economical + technological + cultural)

Finally, the global and instantaneous style of modern communication means that none of the above exhibits any regional variation. Key information that disparate communities once had to systematically derive on their own or through word of mouth is now simply available. The example of regional flavor erasure par excellence is the movement of FM radio away from independent broadcasters whose particular tastes and quirks could shape entire regions (and make/break artists in the process), toward media conglomerates like iHeartMedia (formerly Clear Channel) and Sinclair Broadcasting Group who pump the same content to all their affiliates worldwide. This is smoothing.

Side by side comparison of the most recent Cannibal Corpse album cover and the new Taylor Swift album cover. Below, side by side comparison of both artists’ social media accounts. This is smoothing

Smoothing does exactly what its name suggests: it takes the rough edges away, unifies dissimilar objects, and uniforms them in one monochromatic, soylent glop. Notice in the above example that the stark differences in content have been minimized and the overall style and structure of presentation has been unified by the platform (in this case Instagram, but also true of Spotify et alia). Even the air of emotional underdevelopment, which is maybe the one characteristic that these artists share in common in the first place, is all but obscured by the structural veil imposed by the platform.

I could include a screenshot of my own profile, but it looks more or less identical. What recourse does an artist have in this new, smooth age?

Kill Your Idols

The medium may indeed have a message of its own, separate and/or in conjunction with its content. And while it is important to “stay woke” to the subliminally persuasive elements of such a message, I’d like to point out that there is a useful historical—even mythological—component to the message as well.

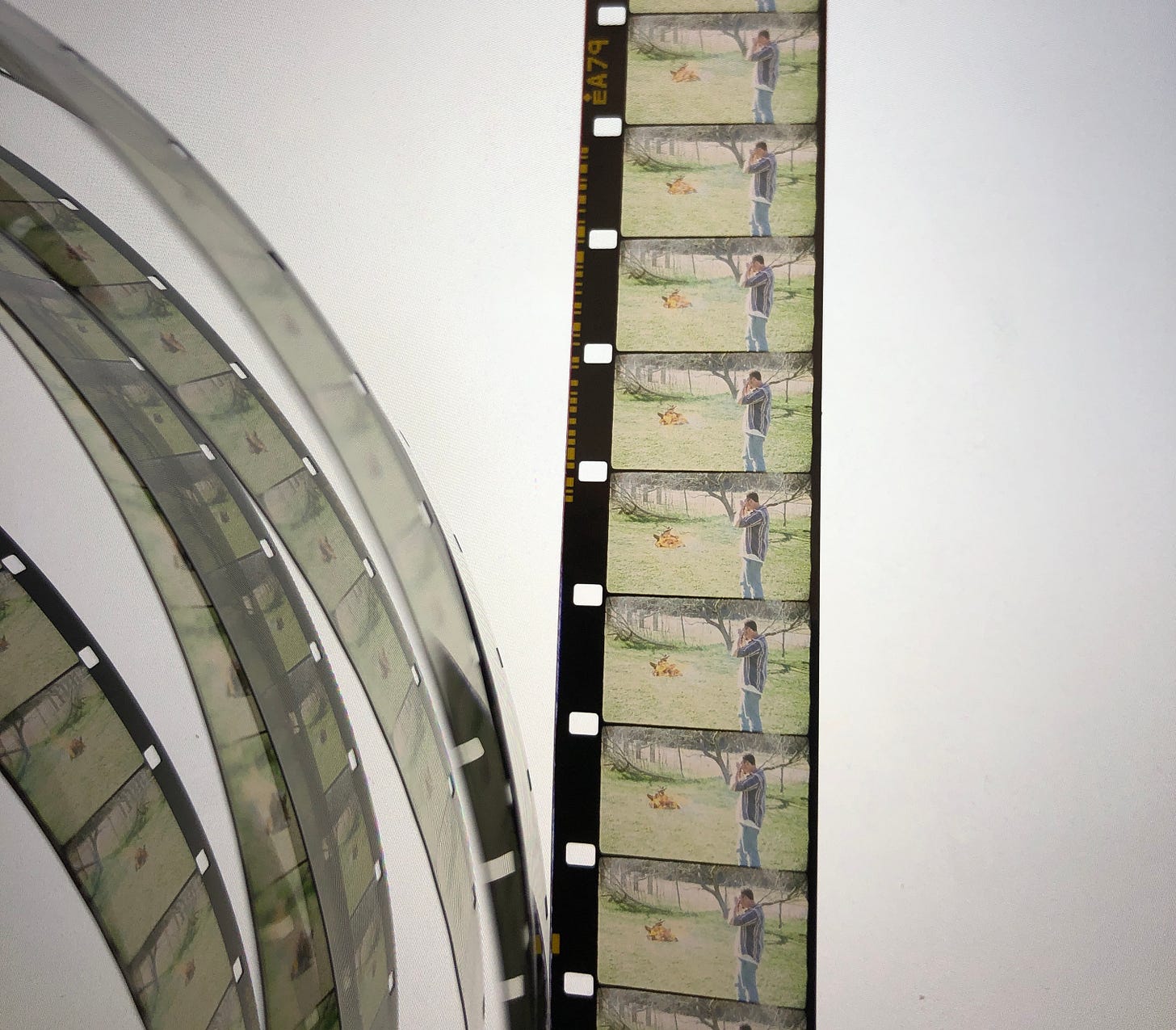

Kodak Ektachrome 100: 16mm color reversal film

I’ve been working with 16mm film for about a year now, and I’m totally in love with the format. 16mm is almost as old as the movies themselves, but it really took off in the middle of the 20th Century. The new medium of broadcast television meant that there was a new need for TV-sized content, and it quickly became standard use for news, documentaries, educational/training films, and independent film productions. Because it is half the physical size of 35mm, it costs—you guessed it—exactly half the price.

I’m particularly interested in the intersection of 16mm film and music. Being the format of choice for budget-conscious filmmakers and especially documentarians, it turns out that much of the iconic imagery that we associate with (particularly live) music from the 20th Century was shot on 16mm, all the way through the 1990s.

The iconic rooftop performance of the Beatles shot on 16mm for “Get Back” in 1969. Dig the guy in the background holding an Arriflex 16BL—I have one of those cameras! Photo by Apple Corps

David Bowie as shot by D.A. Pennebaker for what turned out to be the final show of the Spiders from Mars (1973)

Lightnin’ Hopkins as shot by Les Blank for The Blues According to Lightnin’ Hopkins (1970)

Madonna backstage in Truth or Dare (1991) with concert sequences shot in color on 35mm film. Gorgeous!

It seems to me that the structural components of 16mm—the aspect ratio, the noticeable grain, the color, the flatness or compressed look of film, in other words, some of the “vocabulary” of this particular medium—combine to create a holistic effect that is greater than the sum of its parts. That effect accomplishes the task of not just documenting the subject, historicizing the subject, but also of mythologizing the subject. Why?

Well, it could be that a film that requires a director, a camera person, a sound person or two, an editor, etc., plus a whole lot of money, all in service of a particular subject, lends to that subject an air of importance.

But I think the mythology is baked into the medium itself: by photographing a subject with a particular set of tools (cameras and mics), technology (motion picture photography), and science (film emulsion/development chemistry), you essentially affirm a belief that your subject is equivalent to other subjects which have been treated in the same way.

This legitimization via the medium is the same thing that draws someone like myself to produce a vinyl record: by committing the money and the energy to bring a record into the physical world, you inevitably make that record “canonical” in the grand scheme of recorded music.

Whether or not any of it matters to The Culture is moot because The Culture has already accounted for your offbeat creative choices by smoothing. Want to show your 16mm film to virtually anyone? Unless you’re planning on carting a projector from house to house, your only option is to upload it to a platform which is going to render it as one of billions of tiny little thumbnail images and drop it in someone’s feed after a video of a person eating a spoonful of ground cinnamon but before another video of a person arguing in favor of genocide. Smooth.

Mythologize Your Friends

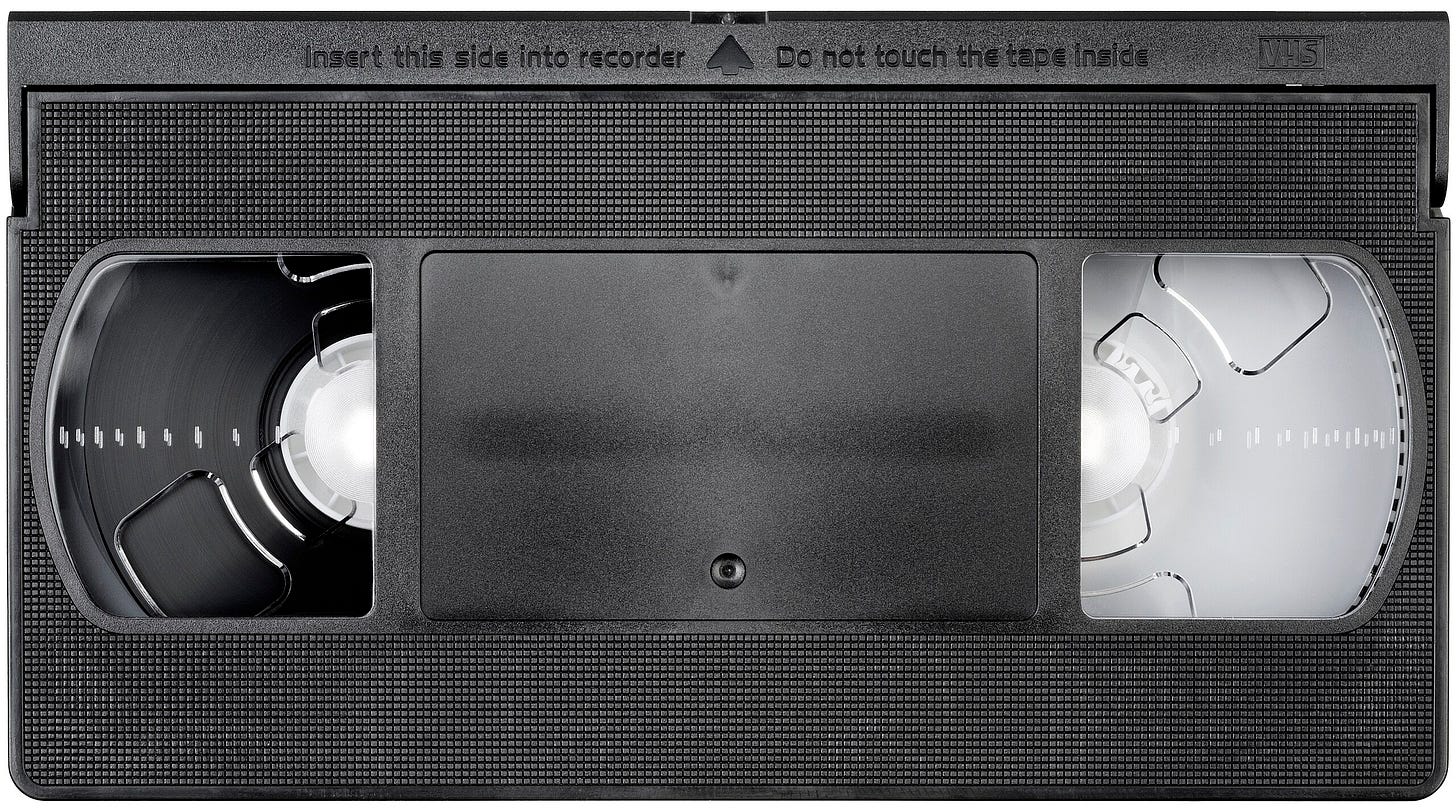

Because ideas and objects move through culture in a circular fashion, we are always at a point where certain media are, by definition, “counter-cultural.” My perception in my short time here is that this rotation is highly influenced by nostalgia for a pre-natal past that is idealized by up-and-coming culture creators (let’s say 15-25 year-olds) who have discovered the ephemera of their parents from when they were 15-25. When I hear that Zoomers are getting into Hi8 and other video tape formats for their “aesthetic,” all I can do is cringe as I remember just how disappointing those images looked to me as a teenage boy who desperately wanted to make a cinematic image—a mythological image!—but did not have the tools to understand why even the latest and greatest Sony Handycam did not do that and never would.

But we shouldn’t just write off younger folks’ creative choices because we disagree with the medium, especially if a preference for that medium develops in response to the pale, flat, smooth mainstream. In fact, the whole point of this essay is that this should be encouraged! I think there is something to the pre-natal aspect here: perhaps the videocassette format does feel mythological to Gen Z because it comes from the pre-natal past just like myths do. Could it be that there is always some amount of fetishizing a past not experienced, whether it was 10, 100, or 1000 years before birth?

And Zeus said to the people of Athens, “I bestow upon you the Video Home System format! Make sure you tape over this before you watch any of it, I used to use these up on Olympus in my Swan Era to—you know what, never mind.”

“Ugh, we threw hundreds of them away when we switched to CDs,” said my parents when I brought my first vinyl LPs home. “No more skipping, no more pops!” From their perspective, CDs were qualitatively (and provably) better. From my perspective, LPs were bigger, heavier, made of beautiful printed card stock instead of plastic jewel cases… and you had to go to a disgusting dusty shop that reeked of cigarette smoke and get filthy to find the ones you wanted. They were, in the year 2004, counter-cultural. Now Taylor Swift presses 8 different colors of the same record, her fans buy the same album 8 times, and you can even order one from Walmart dot com. Or if you’re feeling particularly rich, snag a couple of her records from just a few years ago for $3,000 a pop. Circular.

But while concepts and trends may recycle in the constant churn, I’m not optimistic that a new medium of telecommunication will break through and replace the internet. After all, the internet is capable of accommodating the content of almost every other extant medium, provided it’s been smoothed enough (and optimized for 9:16 vertical video. Gag.). My suggestion in light of this is to not wait around to mythologize your own subjects—including yourself—in whatever format suits you. Whether they are people, animals, places, or things: photograph them, paint them, sculpt them, film them, record them, write them into a book, poem, or song. No one else is going to do it. Don’t let the waters of the mainstream dissuade you from trying something different, expensive, or hard. Don’t let them erode the sharp edges that make your work unique to you. Resist being smoothed. Resist accommodating media platforms by hewing to their style, format, size, etc. Resist the tools they develop—the funny filters, the audio clips, the video duets—this is all noise and all it does is obscure signal. The mainstream will eventually smooth even these platforms, and new ones will arrive to replace them. Just make things, and art will follow.

What Am I Watching?

“I’m a very special person. I’m noble. And splendid.”

Burt Lancaster’s Ned Merrill is a myth in his own mind, but you wouldn’t know it from how the The Swimmer begins. It starts in media res, with Lancaster fulfilling the promise of the title from practically the first shot, and by all accounts he is beloved by his back-slapping, hand-shaking, cheek-kissing peers. Lounging at a neighbor’s pool in the opening scene, he looks across the valley at Westchester County, NY and realizes that he can go from property to property, from pool to pool, and “swim” his way back home.

What follows is a series of increasingly surreal encounters with neighbors who raise questions that initially seem benign—where have you been all summer? How are your wife and daughters?—but start to pile up and paint a drastically different portrait of this “very special person.” Lancaster himself never appears in more than a Speedo for 95 minutes (and sometimes less than that), a bold but exceptional choice at age 55.

Based on a short story by John Cheever, The Swimmer was plagued by its producer Sam Spiegel, who eventually took his name off the film but not before firing director Frank Perry, recasting half the film, and having Sydney Pollack reshoot a huge chunk of it in California. Which is kind of a shame, because by all appearances, husband-and-wife director/screenwriter duo Frank and Eleanor Perry had whipped up a pretty unique treatment of what’s been called Cheever’s best short fiction work.

We’ll never know what The Swimmer could have been if the Perrys had been left alone or paired with a more sympathetic producer, but what we have is still pretty unique. I’m writing this recommendation about an hour after watching the film, and I just can’t stop thinking about how it made me feel. It’s the kind of movie that would never be made in Hollywood today and one that ends with more questions than it started with; my favorite kind of film.