The Production of the Production, Part 2

Earlier this summer I wrote about my process for preparing to shoot a music video from scratch. I’m happy to share that the video is released this week, and you can watch it RIGHT HERE. If you like the music, be sure to consider my hamburger analogy, and in doing so I hope you decide to show some support to Talking With Hands.

It’s now time to tell the second half of the story.

Chapter 1: Production

My first article was focused solely on pre-production, and with good reason: at the time of writing, we had not actually started doing anything, although it should be apparent from that article that much work had indeed been done.

I picked up Matt from the airport around noon on a Friday, and we stopped at a trailer next to the highway to get some tacos pa’ llevar. He would be flying out before noon on Sunday, which meant that we had basically the rest of Friday afternoon and all of Saturday to film. It shouldn’t really take more than a day to make a music video, but we were shooting motion picture film on an antique camera, there was to be effectively only one crew member (me), and at that moment I had specified almost 50 “set-ups” in my shot list.

An excerpt of the shot list for this project. Each one of these line items requires its own camera “set-up,” meaning positioning the camera, framing the shot, lighting the shot, and shooting the shot. For help with conceptualizing the flow of the piece, I added notes about angle, camera movement, etc. Compare this excerpt to the final cut and see what you think.

Perhaps one of the most underrated and under-appreciated credits on a given film is the “production designer.” We tend to think of the creative responsibility in filmmaking in terms of directors, writers, and sometimes actors or cinematographers. But in truth, none of those people has anything to point a camera at without the production designer. This person is in charge of the entire team of artists and craftspeople who build, paint, and furnish sets; design and fabricate costumes; build props; choose colors. Of course, the high-level decisions are ultimately prescribed and approved by the director and/or producer, but all films owe their “look” (at least, the look of the world they strive to depict) to the production designer. Next time you’re watching anything, look for that person in the credits; it’s all but guaranteed that you’ve never heard of them.

Our need was to build a set in a garage that, fortunately, was supposed to look like a garage. It had to be a home workshop/laboratory of sorts, which meant it had to feature a desk or workbench around which most of the action would coalesce, and this workspace had to have just the right amount of order/disorder to look “real.” On top of that, the set should be built in a way that facilitates moving a big camera and tripod rig through it. It needs to be real enough to look real, but fake enough to be essentially disposable. It’s a good thing my garage is already strewn with tools, materials, and usually multiple projects at various stages. Many of these things we just relocated to our set position and arranged in such a way to look like they were all in use.

It was hot in Texas in July (surprise), but as we worked with the garage door open and the fans whirling, a completely uncharacteristic summer rain storm blew in and drizzled softly behind us throughout the afternoon. I took this as a good omen.

The majority of the film’s action was meant to take place late at night, and while I had blacked out the garage windows so that we could shoot all day Saturday, I wanted to take advantage of our first night together and start knocking some things off the shot list, especially the first two shots that called for a pitch-black setting.

Now was the moment of truth: there was no question by this point that work had been accomplished, decisions made, money spent, flights booked, etc. But it was time to start committing that work to film—irreversible, un-erasable, expensive film—which, at the end of it all, would itself be the only actual evidence of any work whatsoever. All creative projects reach this moment, whether it’s the first brush stroke, the first downbeat, or the first “action!” How the production navigates this necessarily clunky and unfamiliar moment is crucial to the results: do you clear the hurdle, enter a flow state, and move forward without ever looking back? Or do you stumble, hit a wall, lose the focus, and start to doubt the entire enterprise? In either case, the first moments are always going to be ones of discovering how everything will go for everyone involved. In his 1986 book On Filmmaking, even the great noir director Edward Dmytryk says, “I have never made a film without wishing I could reshoot the first few days’ work.”

On a project smaller than a feature film, like one that only shoots for a single day, you still have to navigate this early period of indecisiveness and ambiguity. Perhaps the most important thing is to silence any doubt. This, I’m afraid, is a skill that everyone has to learn on their own. Here’s Dmytryk again: “Every member of the crew recognizes indecision and insecurity. If the director exhibits signs of either… the entire crew, from the cameraman on down, is immediately affected… To suffer from butterflies is no sin… but it is a sin to show it to the world. Above all… leadership is what a director must demonstrate, even if he has to stage an act of his own.”

Like my friend and sometime producer Chris Schlarb, I’m a big fan of enforced creative limitations; boundaries can help shunt the production through this most difficult phase (and others). One of our boundaries for this shoot is that we were working with analog film. Shooting on film means that you can’t see the final image until weeks later. After the camera cuts, there is no review of the footage, and you have no other choice but to move to the next thing. With your decision-making narrowed, you move forward. Do this often enough, and you develop a sense of trust in your instinct and ability. I’m convinced that working in an instantaneous digital space where you can immediately review the results and decide whether to proceed or re-do something causes no small amount of turning in circles, spinning wheels, and wasting time.

Depending on the nature of the project, one workaround for this early, ambiguous phase is to start by doing the “easy” things. The shot list should be helpful here, but it alone cannot hoist you past the decision of what to shoot first. We started on Friday night by grabbing insert shots and close-ups. Reach out and turn the computer monitor on. Pull on that cable. Flip that switch. Basic movements that require no acting ability and barely any sense of timing. Slowly, things started to disappear from the shot list until more complicated set-ups were all that remained. But by that time, late on Saturday afternoon, we had entered the flow state and it was not a question of “if” we were going to be able to pull it off, but (slightly) more simply, “how.”

From set-up to set-up, lights and set pieces need to move. In the second photograph, the lighting has become more surreal in accordance with the narrative, and we’ve completely eliminated our “laser testing chamber,” a whole computer monitor, and one of the wood pallets so that I could get into position with the camera and grab the correct angle. Of course, you’ll never see this erasure (or question the camera position) in the film itself. Moving people or objects for the camera’s sake is called “cheating”—as in, “cheat your head to the left a bit.” It may not feel or look natural in-person, but to the camera it will look great.

All in all, we shot 300 feet of film, or just about nine minutes. The song is a little over three-and-a-half minutes long, so our “shooting ratio” here is about 2.5:1, meaning that every 2.5 feet of shot film resulted in 1 usable foot of film in the final cut. Back in the heyday of 16mm film, a shooting ratio of 5:1 was considered “economical.” Most motion picture films averaged more like 20:1, and if you were a Kubrick or a Coppola, well…

You have to keep in mind that the ratio here also includes the brief moments that it takes for the camera to come up to speed, slow to a stop (the “ramp up/down” time) and any amount of extra footage that passes before “action!” is called. The point I’d like to make is that 2.5:1 is an impressive ratio to achieve under any circumstances. As I told Matt before we started shooting, “there are no second takes.” Of course, I was able to squeeze a couple of mulligans in, but most of what you see here are the first and only takes, including the climactic slow-motion fireworks shot. This shot was achieved by running the camera at its fastest speed of 50 frames per second, which was slowed down to 24fps on playback.

By the end of Saturday, we felt exhausted and high. I’ve come to associate this feeling with creative work well-done. Being too tired to move but too energized to sleep is something I’m familiar with from making records too, and this kind of frenzied neural state has always, in my experience, boded well.

Chapter 2: Post-Production

Nearly a month passed. Matt went back to Los Angeles, and I went to Rhode Island for the Newport Jazz Festival. Midway through my trip, the footage showed up in my inbox from the film lab. This moment is never not exhilarating and terrifying—in fact, as I write this paragraph I am expecting to see some new footage shortly (for a different project), and I can feel my pulse quickening just thinking about it. It’s also surreal: there is no sound recorded on motion picture film, and watching silent, unedited images pass by in exactly the order they were captured prompts all kinds of strange thoughts. Some things look exactly as you remember they looked through the viewfinder, some things look better/worse, and some things look otherworldly—the unique properties of film and light (and time) combine to reveal something that may not have ever existed, even though you’re staring right at the visual evidence.

The next and final phase is somewhat of a misnomer, because during “post-production” you are absolutely still working on the production of the thing. It’s also paradoxically where the film is really made. Up to this point, we’ve dreamed, designed, and even created a bevy of images, but there’s still no film. Orson Welles once told the magazine Cahiers du cinema, “the only time one is able to exercise control of the film is in the editing room.”

This can be a blessing, a curse, or both depending on who’s holding the reins. Welles was notorious for slowing down to a glacial pace once he had reached the editing phase, and his entire career was demonstrably plagued by his own particularities in this regard. To me, editing is a blissful phase. The software is complicated, to be sure, but dragging clips around on a laptop is exponentially faster than cutting film by hand, and it allows for more intuitive, “gut” decision making than perhaps any other phase in the filmmaking process. When you strip away some of the technical decisions you have to make about cropping, aspect ratio, color correcting, etc., we’re really just talking about selecting the order of things. Consider:

Shot 1: A young lady looks nervous and glum on an empty train platform

Shot 2: A train arrives, and people pour out of it

Shot 3: The young lady now looks excited, expectant, and vibrant, and we see her smile widen as she looks out-of-frame and notices something

In this sequence, it’s pretty clear that the arrival of the train and the people on it are positively received—perhaps she’s expecting someone important, and the arrival of that person has released the tension she felt before they got there. But by simply switching shots 1 and 3, you present the exact opposite scenario. An excited young lady watches the train come in, and now that it’s gone she looks nervous and glum. We can easily imagine the reason why. Nothing about the photography has changed except the sequence of images. While all images have unique symbolic and metonymic properties of their own, the ultimate meaning of a film is derived from the sequence of its images.

The editing phase is also about coming up with creative solutions to problems that had not previously existed (or were as-yet unidentified in the pre-production phase). Maybe a crucial shot didn’t turn out the way you hoped, or you realize you’re missing a key link between two visual signifiers. In the big-budget world, this is where reshoots come into play. But in the no-budget world, when the artist has already flown 2,000 miles back to their home, you have to improvise. The sequence is endlessly malleable, and each editor will approach the puzzle of raw footage differently. It took Walter Murch an entire year to cut Apocalypse Now from 1,250,000 feet of film (~230 hours). Ending up with a film that ran two hours and twenty five minutes meant that for every minute used in the finished film, 95 minutes went unused (a 95:1 shooting ratio). In his words, editing “is not so much a putting together as it is a discovery of a path;” any other editor would have discovered a different path through those 230 hours. To me, this is encouraging. I’ll hazard an absolute when I say that there isn’t a single film that hasn’t been “saved” in one way or another in the editing room. Just like with painting or with music, there is no perfect sequence of moves that results in the final product; you will always make creative decisions in the service of repairing mistakes or altering your expectations of the original vision. The amazing benefit to the creator is that the audience will never know which decisions were made out of necessity and which were made for creativity’s sake.

In the past year, I have edited no fewer than seven pieces ranging from 30 seconds to 17 minutes, and I can say without a doubt that I love doing this work. Like a lot of work that I do in the music, writing, and radio worlds, the quality of the edit seems to be directly proportional to how invisible it is. In other words: bad work stands out, and the greatest work flows through your consciousness effortlessly. The goal is not that the audience be aware that they are experiencing something great, but that they just actually experience it.

The editing suite. On the left is a “scope” that shows the overall brightness of the image currently in the center. On the right are controls to alter the colors. The main sequence of clips is arranged on the bottom with the audio of the song underneath. Subtitles and/or cutaways are easily stacked on top of the main timeline.

The final steps in the process involve treating the color of the raw footage. The goal is not just to make sure all the shots match each other in terms of contrast, saturation, and exposure, but also to give the entire piece its own, unique “vibe.” This work is usually done by a professional colorist, much the way a record gets sent off to a mastering engineer as its final step. But here again we DIY. The role of colorist has become much more significant in the modern digital era, where footage comes out of high definition cameras looking very flat and uninspiring and needs to be treated in order to look anything like a film as we know it. Fortunately for us, the medium of analog film imparts its own unique texture that many have tried to replicate with plug-ins, filters, etc. I pushed the colors around a little bit, but I mostly tried to stay out of the way of the film, letting it shine in all its gritty, grainy, film-ness.

So: how did we do?

What Am I Watching?

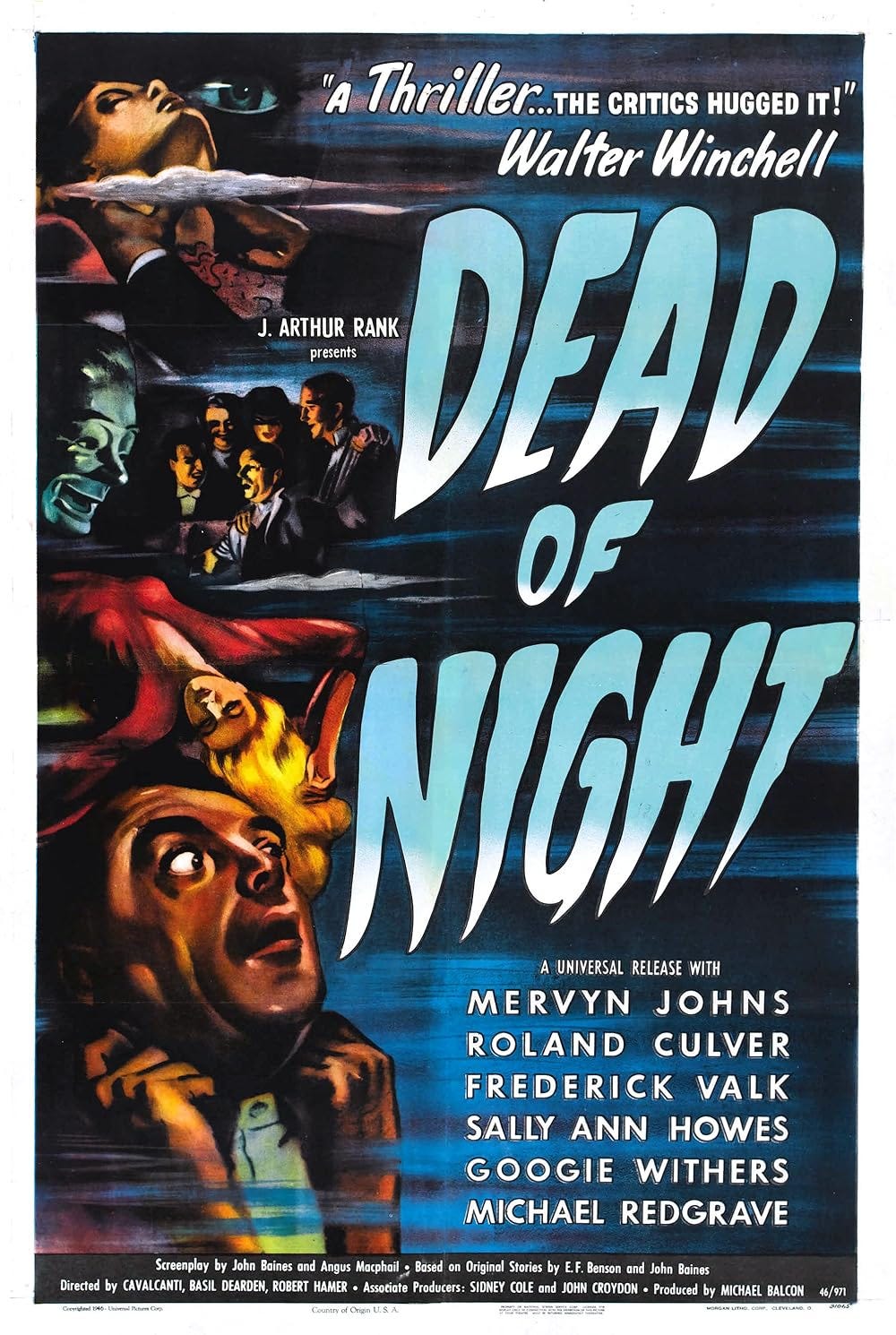

October is the spooky season, although I am a year-round horror fan. Dead of Night (1945) is one of the first British horror films and (to my knowledge) the first “anthology” horror film, presenting us with a handful of spooky shorts that all tuck into a frame story that is as harrowing as any of them.

An architect is called out to a country house for the weekend to consult with the owner on its restoration, but as he arrives at the house he has the unsettling feeling that he’s been there before. Inside, a handful of guests are gathered for afternoon tea, all of whom seem familiar to him. He doesn’t waste much time informing all of them (and us) that yes, he has met them before, in a dream. The dream turns into a nightmare, though he can’t remember why. One of the guests, a hokey European psychiatrist from central casting (vaguely Germanic accent included), spends most of the film explaining how this is a simple case of déjà vu. But as the architect increasingly (and correctly) predicts small things about the future (“It’s later on, we’re having drinks, and you break those glasses of yours”), all rational explanations fall by the wayside. The guests, intrigued and excited by this stranger’s predictions, delight in sharing their own stories of the supernatural, and here we are propelled into the various shorts that comprise the bulk of the film.

The anthology model would become popular in the ‘60s and ‘70s with a series of films produced by Amicus—including the namesake of the later television series Tales from the Crypt—and find perhaps its best iteration in 1982’s Creepshow, although they’re still making horror anthologies well into the 21st Century. In the last few years, Dead of Night has become a film that I revisit when the fall season starts, the mornings have a distinct chill to them, and it’s not too difficult to imagine that I too may be living a circular, nightmarish, British existence.